| INTERSTATE COMMERCE COMMISSION |

| REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR OF THE BUREAU OF SAFETY IN RE INVESTIGATION OF AN |

| ACCIDENT WHICH OCCURRED ON THE LINE OF THE KEY SYSTEM TRANSIT COMPANY AT |

| OAKLAND, CALIF., DECEMBER 4, 1924 |

| JANUARY 12, 1925. |

| TO THE COMMISSION: |

| On December 4, 1924, there was a rear-end collision between a passenger train of the Key System |

| Transit Company and a passenger train of the San Francisco-Sacramento Railroad on the line of the Key |

| System Transit Company at Oakland, Calif., which resulted in the death of 8 passengers nod 2 employees off |

| duty, and the injury of 36 passengers and 2 employees. The investigation of this accident was conducted |

| jointly with the Railroad Commission of the State of California. |

| LOCATION AND METHOD OF OPERATION |

| The Key System Transit line is an electric railway using 600 volts direct current for propulsion |

| purposes; it comprises street-car lines in Oakland and other cities in the East Bay district, and the Key |

| Division, on which this accident occurred, on which trains are operated from junction points with the |

| street-car lines to the Key System Pier Terminal, located 3.85 miles west of San Pablo Avenue, Oakland. |

| At the pier connections are made with ferryboats which are operated to Market Street, San Francisco. In |

| order to reduce the number of train unit operations on the Key Division it is the practice to consolidate |

| trains in each direction between junction points and the Pier Terminal and the trains on this division |

| consist of from one to as many as eight cars. Trains of the San Francisco-Sacramento Railroad are also |

| operated over the Key System tracks from Fortieth Street and Shafter Avenue to the Pier Terminal. The |

| operation of these trains between those points is tinder the supervision and control of the Key System |

| Transit Company. |

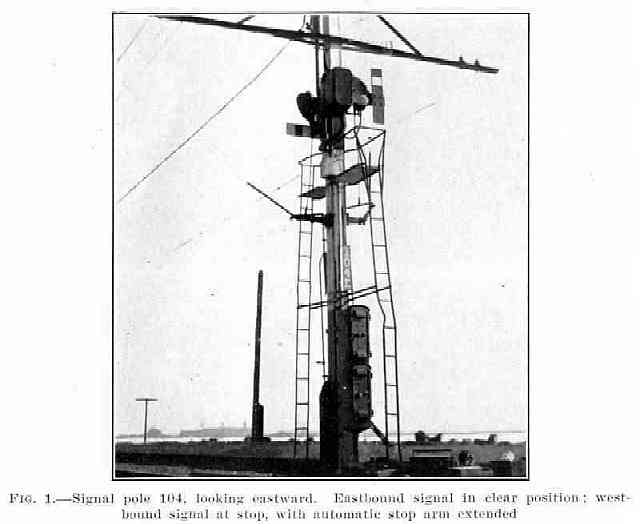

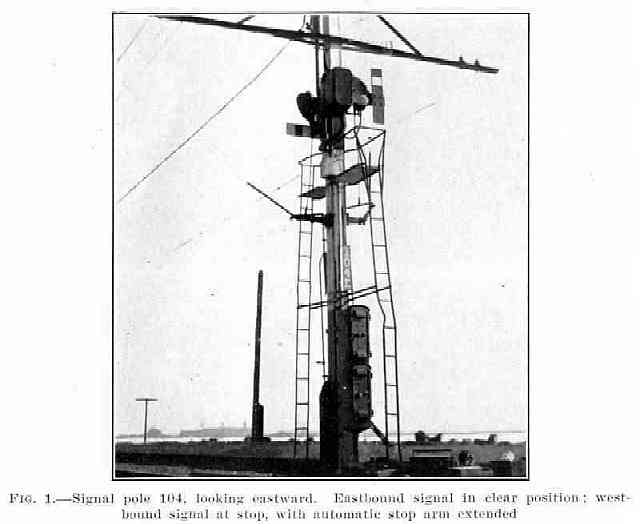

| That part of the Key System line on which this accident occurred is located upon a fill extending |

| into San Francisco Bay. It is a double-track line equipped with an automatic block-signal system combined |

| with an automatic train-stop system. The signals are of the three-position, upper-quadrant type and the |

| automatic train stop is of the overhead mechanical trip type. Alternating current control circuits and |

| single-rail track circuits are used. The signals are mounted on center trolley poles and the automatic stop |

| arm is connected to the spectacle casting of each signal and operates simultaneously therewith. When the |

| signal is in the danger position the stop arm is in position to engage the arm of a valve located on the car |

| roof. Should the car pass a signal and a. stop arm in this position the valve is automatically operated to |

| cause an emergency application of the air brakes. In the vicinity of the point of accident trolley poles are |

| spaced 105 feet apart and signals and automatic stops are installed on each fourth pole, or 420 feet apart. |

| A full-block overlap is provided by the control circuits, which tire, arranged to display one caution and |

| two step signals behind each train. The, arrangement of signals, in this vicinity is intended to provide for |

| the movement of trains trader a headway of 45 seconds and was designed to provide adequate braking distance |

| for Key System trains which with the propulsion current used are operated at a maximum speed of |

| approximately 36 miles an hour and at this speed require, a distance of from 300 to 350 feet in which to |

| stop. |

| Signal 104 is located 11,321 feet west of signal 46 at tower No. 2. Approaching the point of |

| accident from signal 46 the track is tangent for a distance of 6,197 feet, then there is a 30' curve to the |

| right |

| 633.72 feet in length, followed by 4,491 feet of tangent to signal 104, the tangent extending a considerable |

| distance beyond that signal. The accident occurred practically opposite signal 104, located at a point about |

| 1 1/4 miles cast of the Pier Terminal, at about 7.54 a.m. |

| At the time of this accident a light rain was falling and the range, of clear vision was limited to |

| a distance of approximately one-half mile. |

| DESCRIPTION |

| The trains involved in this accident were Key System westbound train No. 729 and San |

| Francisco-Sacramento westbound train No. 15. Train No. 729 was a consolidated train of the Oakland Twelfth |

| Street line and consisted of four center entrance motor cars, Nos. 655, 656, 664 and 665 in the order named, |

| with Conductor Noone and Motorman Compton in charge. The motorman of this train reached a Caution Signal |

| indication, at signal 104 on account of preceding (rains being delayed due to switching operations at the |

| Pier Terminal. Approaching this signal Motorman Compton shut off power and when about opposite pole 106 |

| applied the brakes for the purpose of bringing his train to a stop; the train stopped with the head end some |

| distance east of signal 100, which was in the stop position, and the rear and practically opposite signal |

| 104. While standing at this point the rear end of this train was struck by San Francisco-Sacramento train |

| No. 15. |

| San Francisco-Sacramento train No. 15 consisted of motor car 1014 and was in charge of Conductor |

| Knoblock and Motorman Brubaker; this train was en route from Concord, Calif., to Oakland Pier Terminal. |

| The last stop made prior to the accident was at tower No. 2 on the Key Division, where it was stopped at |

| signal 46 and held until two Key System trains had proceeded toward the pier. After train No. 729 had |

| cleared, the route was lined up for train No. 15; that train then proceeded toward the pier and while |

| running at an estimated speed of about 20 miles an hour collided with the rear end of Key System train No. |

| 729, which was standing near signal 104. |

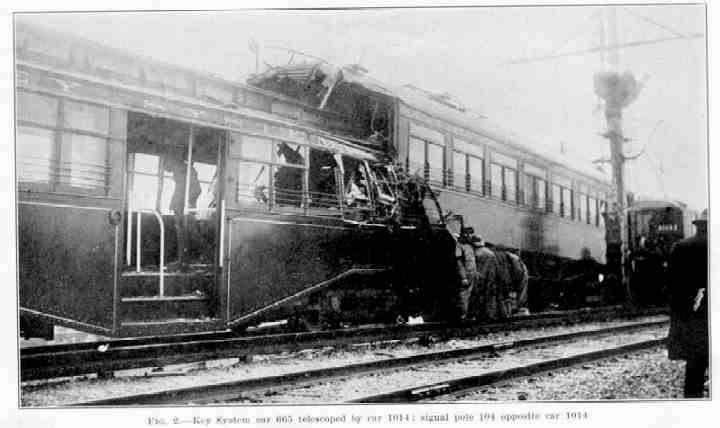

| Motor car 1014 telescoped the rear car of train No. 729 for a distance of 18 1/2 feet. It came to |

| a stop with the head end of car 1014 at a point 31 feet west of signal 104, and the rear end of car 665, the |

| last car of train No. 729, was 18 feet 6 inches west of signal 104. |

| Car 665 was constructed with steel underframe, steel side frame and steel body plates, having |

| wooden lining and wooden roof construction. It was 7 feet 7 1/2 inches long, weighed 60,000 pounds, and the |

| distance from top of rail to top of 8-inch buffer beam was 48 inches. The rear portion of this car was |

| practically demolished, the damage probably being due in part, at least, to the fact that the floor line and |

| top of the body butlers were lower than the floor and buffers on the San Francisco-Sacramento ear. Motor |

| car 1014 was of steel-underframe construction, having wooden superstructure. It was 57 feet 10 inches long, |

| weighed 93,260 pounds, and the distance from top of rail to top of 8-inch butler beam was 53 inches. The |

| platform of this car over rode the floor of the Key System car. The forward end of car 1014 and a partition |

| 7 feet from the head end were demolished, pipe. connections and other equipment broken or torn from the car, |

| and the truck on the damaged end was driven backward about 10 feet, bending foundation brake gear rods and |

| causing other damage. The trading pair of wheels of this truck was derailed. |

|

Key System car 665 telescoped by car 1014; signal pole 104 opposite car 1014. |

| Interior of car 665 after separation from car 1014. |

| SUMMARY OF EVIDENCE |

| The employees injured were Motorman Brubaker and Conductor Knoblock, of train No. 15. Motorman |

| Brubaker, on advice, of counsel, refused to testify and declined to give, a statement of any character, on |

| the ground that anything he might say could be used against hint in criminal proceedings which were thought |

| to be pending. |

| Motorman Compton, of train No. 729, stated that on the morning of the accident there, was a light |

| rain but the view was good. When he had reached a point practically opposite signal 108, he, saw that signal |

| 104 was in the caution position; he shut off power, made a full service application of the, air brakes, and |

| had no difficulty in bringing his train to a stop before reaching signal 100, which was in stop position. He |

| stated he immediately sounded a whistle signal for the flagman to go back and then released the brakes; |

| within 30 or 35 seconds after stopping he felt the shock of the impact, which moved his train forward a |

| distance of 3 to 4 feet. Motorman Compton said the head end of his train stopped at a point about 130 feet |

| east of signal 100 and he thought the, rear end cleared signal 101 by a few feet. He stated the reason he |

| stopped at that distance from signal 100 was because he made a full service application in order to be |

| certain that his train would not pass the signal, and had he released so as to approach nearer to it before |

| stopping he probably would have, overrun the signal. In making this stop he stated that he shut off power as |

| soon as he saw the caution signal, at which time he was running at full speed, and made, a brake application |

| at about the second pole cast of the caution signal. |

| Conductor Noone, of train No. 729, stated that approaching the point where the accident occurred |

| his train was running at a speed of from 30 to 35 miles an hour, and that it came to a stop with the rear end |

| extending slightly east of signal 104. He was in the rear car of his train. As soon as the train stopped the |

| motorman sounded the whistle signal for the flagman to go back; he took up flagging equipment, got out the |

| center door on the left-hand side of the ear and started back, but the collision occurred before he reached |

| the rear end of his train and without his having seen the approaching train. |

| Brakeman Hamma, of train No. 729, stated that when his train stopped near signal 100 he was |

| collecting fares in the leading car of the, train. He estimated the time of impact at about 30 seconds after |

| his train came to a stop. |

| Brakeman Van Dalsen, of train No. 729, was, in the third car from the head end, and had finished |

| collecting fares. He also estimated that the shock of collision came about 30 seconds after the train came |

| to a stop, and thought his train was moved forward a distance of about 4 feet. |

| Motorman Hobson, who as deadheading on train No. 729, was riding in the motorman's compartment of |

| the third car from the head end. He stated that as soon as the train stopped Motorman Compton sounded the |

| whistle, signal for the flagman to go back; he raised the cab window and on looking toward the rear saw train |

| No. 15 about two car lengths from the rear of train No. 729, moving at a speed which he estimated to be |

| about 30 miles an hour. He realized at once that a collision was unavoidable and as there was not sufficient |

| time to let out he braced himself and waited for the shock of impact. |

| Conductor Knoblock, of train No. 15, stated that from Concord to Fortieth Street, Oakland, his |

| train consisted of two cars; at the latter point the rear car was cut off and they proceeded toward the Pier |

| Terminal with one car, which was in good operating condition. Their train was stopped at tower No. 2 |

| because, of signal 46 being set against them, and he saw train No. 729 leave that point, his own train |

| following about 1 1/2 minutes later. He stated his train made the usual speed between tower No. 2 and the |

| point of accident and he did not see train No. 729 after leaving the tower until just before the collision |

| occurred. Approaching the, point of accident the motorman made, a service application of the brakes, which |

| was followed very closely by an emergency application clue to the automatic train stop valve arm striking the |

| trip arm operated in connection with the signal. He heard the exhaust of air from the automatic stop valve |

| and the emergency application of the brakes resulting therefrom threw him off his balance. He then looked |

| forward and saw the rear of train No. 729 only about two-car lengths ahead. Conductor Knoblock estimated |

| that when the service application was made by the motorman the speed of his train -was from 35 to 40 miles an |

| hour, and he thought that perhaps 30 seconds elapsed before the emergency application occurred. After the |

| emergency application he thought the brakes locked the wheels as the call seemed to slide forward until the |

| impact of collision came. Conductor Knoblock stated that Motorman Brubaker operated train No. 15 from Rock |

| Ridge to the point of accident: he had no conversation with the motorman except a word or two when he got on |

| the train at Rock Ridge, bat there was nothing out of the ordinary in connection with the operation of the |

| train between Rock Ridge, and the point of accident. |

| Motorman Willis, of the train which followed train No. 15 westward from tower No. 2 on the morning |

| of the accident, stated that he operated his train under clear signals at a speed of about 30 miles per hour. |

| He stated his range of vision extended for at least half a mile, and after passing through the subway under |

| the Southern Pacific, Railroad west of tower No. 2, train No. 15 was constantly in view until the time, |

| of. the accident. He thought that, train was running at a higher rate of speed than he was able to attain. |

| Motormen on other trains which were being operated over this line on the morning of the accident |

| stated that the rain did not obscure signals, and that, although the rails were wet, they had he difficulty |

| in properly controlling and stopping their trains in accordance with signal indications. |

| Towerman Corker, who was on duty at tower No. 2, stated that when train No. 15 arrived at his |

| tower it was held about one minute to allow train No. 729 to leave in its regular turn. Train No. 15 left |

| tower No. 2 as soon as the switches were lined up for its route, the signal cleared, and the flagman |

| recalled, which he thought was about 45 seconds after the departure of train No. 729. No exact record of the |

| time of departure of trains from that point is kept. |

| Electrical Engineer Bell, of the Key System Transit Company, stated that the signal circuits are |

| so arranged that when it train receives a clear signal indication the signal remains in clear position until |

| the last pair of wheels passes the insulated joint in the track located practically opposite the signal. The |

| purpose of this arrangement is to prevent the signal and automatic stop arm from assuming the danger position |

| until the arms of the automatic stop valves on all cars in the train have passed the signal. He stated that |

| the body of a Key System car overhangs the rear axle a distance of about 7 feet 6 inches and that the |

| insulated joint at signal 104 is located 4 feet 6 inches west of the trolley pole on which this signal is |

| mounted. Assuming that train No. 729 stopped with its rear axle just clearing the insulated joint at signal |

| 104 there would be two stop signals displayed, signal 104, located practically at the rear end of the train, |

| and the other, signal 108, 420 feet in rear of it; a caution indication would be displayed by signal 112, 840 |

| feet from the rear of the train. Mr. Bell reached the scene of the accident at about 9 or 9.15 a.m., and |

| found that the rear end of train No. 729 after the. collision -was standing 18 feet 6 inches west of the |

| center line of pole 104. The automatic stop arm of signal 108 clearly showed that it had been struck by an |

| automatic stop valve arm, the mark being very fresh, and he removed this arm in order to preserve this |

| evidence. Examination of the valve arm of car 1014 also showed a fresh mark indicating that it had been in |

| contact with the automatic stop-arm. Except for the removal and replacement of the automatic stop arm on |

| pole 104 nothing had been done to the signal and automatic. stop apparatus prior to the investigation and it |

| had functioned properly both before and after the accident. Mr. Bell stated that the signal system had been |

| placed in service in 1911, and that there are approximately 18,000,000 forty-five degree movements throughout |

| each year. During the entire time the system has been in service only four false clear failures have, been |

| reported, the last of which occurred in 1916. |

| Master Mechanic Jackson, of the Key System Transit Company, stated that he arrived, it the scene |

| of the accident about one hour after it occurred; while considerable damage to equipment bad resulted from |

| the collision, examination disclosed nothing which would indicate that the brakes had failed to operate |

| properly prior to the accident. He stated that the channel iron buffer on car 665 was not overridden by the |

| buffer on car 1014 but was driven back over the top of the center sills, at the same time pulling in the side |

| angle-iron sills which prevented the sides of the car from being fanned outward by the telescoping action. |

| Superintendent Thornton, of the Key System, stated that on the morning of the accident trains were |

| being operated in their proper order. Just prior to the time of the accident switching operations at the |

| Pier Terminal required approaching trains to be stopped and there were two trains preceding train No. 729 |

| which were stopped and held for that reason. He stated that he instructs train-service employees of the San |

| Francisco-Sacramento Railroad as to their duties on the Key Division and all motormen understand that they |

| are required to operate their trains tinder clear signals and that the speed of trains is dependent upon the |

| distance of clear vision. He stated that he impresses upon all employees the importance of observing what is |

| ahead of them and the fact that the responsibility in case of accident rests upon the motorman of the |

| following car. He had not had any trouble with Motorman Brubaker on this line except once before, on March |

| 1, 1922, when he was involved in a rear-end collision. |

| General Manager Mitchell of the San Francisco-Sacramento Railroad stated that the operating |

| agreement between his railroad and the Key System Transit Company provides that all equipment, train crews |

| and passengers while on the tracks of the Key System Transit Company are entirely under the control of and |

| governed by the rules and regulations of the Key System Transit Company and officers thereof. New |

| employees of the San Francisco-Sacramento Railroad are required to report to officials of the Key System |

| Transit Company for examination and instructions before they are qualified for service. |

| Superintendent of Electric Equipment Miller of the San Francisco-Sacramento Railroad stated that |

| cars of the. type of ear 1014 are so geared that they can attain a maximum speed of 55 miles an hour when |

| operated by a propulsion current of 600 volts. After the accident the automatic stop valve was removed from |

| car 1014 and installed for test purposes on a similar car, No. 1012. The result of tests in each case, was |

| that the brakes were applied and brake-cylinder pressure of 55 pounds was obtained, the initial brake-pipe |

| pressure being 70 pounds; after each test a period of front 38 to 73 seconds was required for the brakes to |

| release. |

| Examination of car 1014 indicated that prior to the collision the brakes locked the wheels and |

| caused them to slide along the rails as all eight wheels on the car showed flat spots of front 1 inch to 1 |

| 1/4 inches in length. |

| ANALYSIS OF EVIDENCE |

| It is noted from the statement of Motorman Compton, of train No. 729 that he shut off power when |

| he first observed signal 104 in caution position and in order to bring his train to a stop made a full |

| service brake application when at about pole 106. He estimated that the head end of his train came to a stop |

| about 130 feet east of signal 100. However, in view of the length of train No. 729 and the position of the |

| rear end of the last car after the collision, it appears that the, head end of train No. 729 came to a stop |

| approximately 185 feet east of signal 100 and that therefore a distance of 430 or 440 feet was required to |

| make this stop. |

| The evidence clearly established the fact that the signal system operated properly. That signal 108 |

| was in the stop position at the time train No. 15 passed it is conclusively established by reason of the |

| fact that the automatic stop valve aim engaged the trip arm operated by that signal. |

| The evidence also establishes the fact that the automatic stop apparatus functioned to cause an |

| automatic application of the brakes when train No. 15 passed signal 108, the first stop signal which it |

| encountered when approaching the preceding train. The very purpose of the automatic stop system which was in |

| service on this line is to prevent accidents of this character, and the failure of the automatic stop system |

| to prevent the accident in this case was due to the fact, first, that train No. 729 came to a stop at a |

| point which resulted in the minimum braking distance afforded by the automatic train stop devices being |

| provided, and, secondly, that train No. 15 was being operated at a rate of speed which required greater |

| braking distance than the minimum provided by the automatic stop system; a further contributing factor was |

| that the rails were wet and the wheels locked and slid after the brakes were applied by the operation of the |

| automatic stop device. |

| The minimum braking distance provided by the automatic stop system was based upon tests with cars |

| capable of attaining it maximum speed of 36 miles an hour. Train No. 15 consisted of a car capable of |

| attaining a maximum speed of 55 miles an hour. According to the statement of the conductor of this train, |

| the speed at the time the automatic stop device was operated was approximately 35 or 40 miles an hour. In |

| view of the fact that after the brake applications made by the motorman and by the automatic train-stop |

| device the car ran a distance of more than 400 feet, and collided with the preceding train at a rate of speed |

| variously estimated at from 20 to 30 miles an hour, the force of impact causing considerable damage to |

| substantially constructed cars, it is apparent that the speed of this car materially exceeded 36 miles an |

| hour, the maximum speed provided for by the automatic train-stop system installed on this line. |

| Rules governing the operation of trains under automatic block signals on this line provide that |

| proper operation is "to run at an even speed on a clear or proceed signal, which is the normal position of |

| such signal." The, rules also provide that a caution signal "means proceed with caution prepared to stop at |

| the next signal." It is apparent from this investigation that Motorman Brubaker failed to comply with these |

| rules and to control his train as required by caution and stop signals displayed for his train. There is no |

| evidence that the, signals were obscured by rain, but on the contrary there is direct testimony from a number |

| of motormen who were operating trains on this line at the time of the accident that the. signal indications |

| could clearly be seen for considerable distances. In view of the refusal of Motorman Brubaker to furnish |

| any statement in the matter, no explanation of his failure to observe and obey caution and stop signals can |

| be advanced. |

| On the portion of the line where this accident occurred there is no rule prescribing a maximum |

| speed limit. |

| CONCLUSIONS |

| This accident was caused by the failure of Motorman Brubaker to operate his train in accordance |

| with the requirements of existing rules and to observe or obey automatic block-signal indications; also by |

| reason of the fact that trains were operated, and were permitted to be operated at speeds which required |

| greater distance in which to bring them to a stop than the minimum braking distance provided by the automatic |

| stop system as installed on this line. |

| To provide against a recurrence of an accident of this character, the Key System Transit Company |

| should at once establish a maximum speed restriction for all trains operated over this line, which will |

| insure, that any train can be stopped in the minimum braking distance provided by the automatic stop system. |

| All of the employees involved in this accident were experienced men and none of them was on duty in |

| violation of any provisions of the, hours-of-service law. |

| Respectfully submitted. |

| W. P. BORLAND, |

| Director. |